Anything exploring the interaction of two or more cultures gets onto my list. AWA, a collaboration between the Atamira Dance Company and the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra is a movement and music biography of Moss Patternon’s family. His dad worked on the Tongariro Power Scheme, damming central North Island rivers for hydro power. Years later he worked on the Yellow River, in China, where he died. His body returned in a closed coffin denying his family of Te Uru Rangi (a portal to heaven).

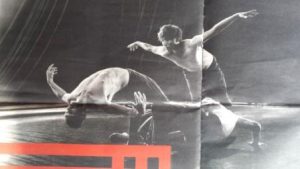

AWA – When Two Rivers Collide, uses Maori and Asian Dancers to create a beautiful tension between two cultures using Kapa Haka and Tai Chi to join the Waikato and Yellow rivers together to powerful effect. The string section of the APO is augmented with Taonga Puro (traditional Maori instruments) and Pipa a Chinese mandolin. Waiata Maori, performed by a children’s choir begins the performance and the focus is shared with a large Chinese choir. It’s an exciting mix, sliding between classical cultures which included Bach and Handel. The dance evokes the myth of Ranginui (Sky Father) and Papatuanuku (Earth Mother) being separated by Tane Mahuta. The dancers work in close contact like flocks of starlings, each dancer taking his turn to lead the conflict, constrained by a dramatic semicircle of cables around the dance area. At times I wanted the dancers to take flight up into the cables, escaping the primordial slime in order to free the spirits. This is not possible with contemporary dance, however, and beautiful as it is, the dancers are limited to delving deep into the floor – grounded with Kapa Haka and Tai Chi elements from which it borrows.

AWA remains a mystery – moving and beautiful. Increasingly New Zealand artists are collaborating to explore cultural relationships as a time when China and Aotearoa are talking trade. This work was well attended and received by a multicultural audience. My hope is that this and similar work will help to break down still prevalent hostility and suspicion amongst Pakeha New Zealanders.

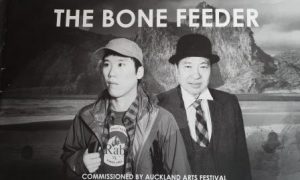

The Bone Feeder began as a play by Renee Liang which was produced in 2010. It’s based on the story of the SS Ventor which left New Zealand in 1902 carrying 499 coffins of exhumed Chinese bodies returning to their homelands in Southern China. The ship was wrecked off Hokianga, finally sinking near the harbour. Coffins and bodies swept ashore were kept by local IWI until a time when they could be claimed by their families. Renee has successfully written an opera libretto for composer Gareth Farr. This is a first for both artists and augers well for future New Zealand opera.

The Bone Feeder began as a play by Renee Liang which was produced in 2010. It’s based on the story of the SS Ventor which left New Zealand in 1902 carrying 499 coffins of exhumed Chinese bodies returning to their homelands in Southern China. The ship was wrecked off Hokianga, finally sinking near the harbour. Coffins and bodies swept ashore were kept by local IWI until a time when they could be claimed by their families. Renee has successfully written an opera libretto for composer Gareth Farr. This is a first for both artists and augers well for future New Zealand opera.

Farr has drawn on his early experience with the Indonesian Gamelan and expanded his composition skills to incorporate Chinese classical instruments – flute, fiddle and zither. A violin, a cello, marimba and Taonga Púoro make up the orchestra.

Young Ben, beautifully portrayed and sung by Australian tenor, Henry Choo meets The Ferryman (Tioti Rakero) and asks to be taken to Mitimiti cemetery where the bones of his ancestor, Kwan and three of his countrymen are excited at the prospect of finally going home. When Kwan sees his descendant, he is reminded of his New Zealand wife. Chinese workers were forbidden to bring their women to Aotearoa and some took local wives, occasionally travelling back to China with money and to produce more sons. Ben, however is part of his New Zealand family so there is a question in Kwan’s mind. Is it appropriate for his bones to return to China? The plight of his Chinese wife, Wei wei is delicately portrayed by Xing Xing, while Chelsea Dolman does credit to Louisa. Together with four other female singers, they create a fantastic and atmospheric chorus. There is a scene where Ben can, in a dream, see Kwan and he is persuaded not to dig up the bones but feed them instead.

Chinese came to Aotearoa with the gold rush and have been here ever since and almost as long as the Europeans. They worked quietly tending their market gardens and selling the freshest fruit and vegetables in small towns all over the country. When the UK joined the Common Market (as it was then) New Zealand looked to Asia for markets, beginning a new wave of immigrants. It is helpful for Pakeha and Maori New Zealanders to be reminded of this long history and to learn, at last, about another culture.