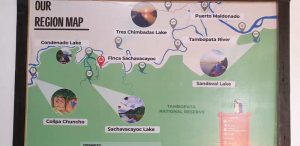

Our short flight from Cusco at 3,399 Metres to Puerto Maldonado takes us down to only 183 metres above sea level and to temperatures of thirty-seven degrees. We are met at the airport by our local guide, Lucy and taken to the tour company offices to store our luggage. We can only take hand luggage on the boat for our three nights up the river. The Tambopata will eventually join the mighty Amazon and the Atlantic Ocean. There is nothing to be seen in Puerto Maldonado, until we get to the river and embark onto a narrow boat.

Our short flight from Cusco at 3,399 Metres to Puerto Maldonado takes us down to only 183 metres above sea level and to temperatures of thirty-seven degrees. We are met at the airport by our local guide, Lucy and taken to the tour company offices to store our luggage. We can only take hand luggage on the boat for our three nights up the river. The Tambopata will eventually join the mighty Amazon and the Atlantic Ocean. There is nothing to be seen in Puerto Maldonado, until we get to the river and embark onto a narrow boat.

We are heading for a resort on the edge of The Tambopata National Reserve. It’s a three-hour journey following the curves of the river. Lucy has an eye for wild-life and re-directs the boatman whenever she spots something of interest. There are families of Capibara the largest rodent, but unlike rats, entirely vegetarian. They are known as the Hippopotamus of South America and like to bask in the river shallows. When startled they scuttle into the dense undergrowth but we manage to get quite close.

Lucy also spots Cayman – the equivalent of Alligators but much smaller. They are extremely wary and dive under the water as we approach. The bird-life includes Herons and Egrets. We also see evidence of slash and burn – a farming practice which is allowed by the government in this so-called ‘Buffer Zone’ around the National Park. The farmers are careful not to clear the river-bank so it’s difficult to tell how much forest has been destroyed. Of even greater concern are the illegal gold-mining dredges common along the river-bank. Fine grains of gold can be found in the river silt and mercury is used to capture the grains. A certain amount of mercury escapes into the water, a poison to living things. Lucy says that government has a clear-out every now and again, but the miners are back a few months later.

I also notice the fragility of the cliffs and evidence of slips into the river, constantly eroding. The river is full of trees which have fallen and along with the soil create hazards and the muddy look of the water.

It’s a long flight of steps up to the beginnings of a walkway which will take us to our Jungle hotel. We meet up with Squirrel monkeys and there are Brown Agouti (another rodent) grazing on the hotel lawn. After settling in, we gather for the sunset and encounter a group of Capuchin monkeys. The local beer is good here and we can put it on a tab to pay later. After dinner I walk to the very end of the walk-way to my hut, setting off solar lighting as I go. The light from my phone fills in any gaps.

This is not malaria country, but we are provided with excellent mosquito nets to sleep under. We plastered on repellent on the river against other biting insects.

We have four am start in the morning so time to sleep.

Day 18 Up the river in the dark

The temperature has dropped somewhat by three thirty when I wake. We are off to see Parrots and Macaws feeding on the riverbank two hours further up the river. We have a packed breakfast and I am amazed at the skill of the boatman, steering up shallow rapids and avoiding sunken logs in the dark. We are not the first to arrive, the shore is already lined with other tourists sitting on lightweight plastic stools staring at the cliffs opposite, some with binoculars and telescopes. We don’t know exactly when the birds will arrive, but we are in good time and they soon gather.

The Parrots come first then the Macaws. They are cautious, watching out for predators which would most likely be monkeys. All is well, and they descend onto the yellow cliffs and start to eat the clay. Their diet is low on Sodium and the clay has plenty so they have adapted their behaviour accordingly. It’s an amazing experience watching these magnificent birds through Lucy’s telescope. There are three different colour combinations: blue and yellow then two versions of red, yellow green and blue. The parrots are green. Every now and then an alarm goes out and they swoop up into the air in a magnificent display to roost on the highest trees. Eventually they all pair up and wander off to do whatever they have to do.

We travel further up the river for a swim. It’s considerably warmer that Lake Titicaca but quite shallow and of course brown. Lucy has swum in the river and assures us there are no Piranhas or Cayman here. We stop for a packed lunch before heading back down-stream.

It’s siesta time until our jungle walk. Lucy points out mostly insects but there are giant Ficus trees which have grown up around a tree. The host has now died and rotted away to leave the Ficus supported by its cathedral – like arches. Suddenly Det wants to know about a hole in the forest floor. Lucy says it’s a Tarantula burrow, and prepares a twig to tease it out. They are apparently not as dangerous as imagined but we are pretty impressed.

Later we are again witness to the sunset as we set of on our night-time Cayman hunt. Lucy has an instinct for knowing what to look for and sure enough we get up close to these ancient creatures who pretend they are invisible by keeping still. Eventually, they panic and leap into the water.

Day 19 Fishing

Not such an early rise today, a four-forty-five start, in time to greet the dawn over the river. We are heading to an oxbow lake, which everyone claims to have learnt about in Geography. It’s a bend in the river at some time cut off and abandoned, leaving whatever lived there to adapt and survive.

It’s quite a walk through the jungle observing the forest and the creatures which live here. The unmistakable remains of cow dung can be seen and Lucy says that the fences are clearly not working. She has already pointed out to us the razor-sharp spines on the fronds of a palm tree, which the Amazonians use as darts on their blow-pipes. She’s also shown us a very ordinary plant which has anaesthetic properties. When these leaves are ground into a paste and the darts charged, an animal on a branch can pass out and fall to the ground. It’s not quite the story told, of poisoned darts, when I was a child but I do wonder what happens if the cows get to eat these leaves.

The lake is calm and serine, we are the only people around. Two very basic catamarans are tethered in the reeds and our boatman takes a long pole and pushes us out silently along the edge of the lake to observe weird looking birds and shags, drying their wings in the weak early morning sunshine.

Suddenly, there is another boat on the lake and a third, further up. We stay close to the edge and eat our breakfast. Lucy and the boatman have brought sticks and nylon thread which get turned into fishing rods. Red meat is on the hooks and we proceed to fish for Piranha. I can feel them nibbling and the trick is to jerk up the rod to get the hook embedded, but my reactions are not fast enough and they nibble abound the hook leaving it empty. I’ve never been keen on catching fish you don’t intend to eat, so I’m relieved that my efforts are unsuccessful.

There are enough Piranha being caught for me to see how aggressive they look with such huge teeth. Just maybe, they rely on this daily feed of meat from tourists to survive, and maybe the shags eat the Piranhas for lunch. On the way back to the river, we come across the runaway cows who seem to know exactly where they are going.

Back at the lodge, it’s time for siesta before a late afternoon boat ride for beer on a beach, encounters with more Capibara and another sunset experience. We finish with a night walk in the forest.

Monkey

Lucy wears a head-lamp, which can switch to ultraviolet light so we can see an otherwise invisible scorpion. Two days in the rainforest has been enough for me to realize the fragility of this ecosystem and how precarious it is living here. Plants need to climb up a large tree to reach the light and there’s a tree which can move sideways to do the same.

When a giant falls, saplings which have been waiting patiently for decades, suddenly leap into growth in a race to command the light. The natural action of the river erodes the edges of the forest which falls into the water, carrying silt and vegetation down-stream. Meanwhile, the tectonic plates underneath the Andes continue to push upwards.

When a giant falls, saplings which have been waiting patiently for decades, suddenly leap into growth in a race to command the light. The natural action of the river erodes the edges of the forest which falls into the water, carrying silt and vegetation down-stream. Meanwhile, the tectonic plates underneath the Andes continue to push upwards.